History of Taste: A Journey into Ancient Egyptian Cuisine (Part I)

Happy new year my readers! I am back after a long break, but as promised in my previous blog, I will come back with something delightful, so here I am. After a lot of research I decided to write about the history of the entire ancient Egyptian delicacies. What's the pattern of their foods? How have various dishes evolved? And when and where they prefer to eat what?

The information I got is so indulgent that you will feel you are living the moment and going to taste palatable items right now! I know it will be overwhelming for you, I have divided my blog into 2 parts.

So no more waiting, prepare your taste buds for a voyage through the ages, where the spices tell tales, and each bite is a chapter in the epic saga of Egyptian cuisine. Get ready to embark on a sensory adventure that transcends boundaries and leaves you with a deeper understanding of the flavors that have shaped a nation's identity. This is not just a culinary exploration; it's a celebration of a culture's resilience, a testament to the enduring legacy of a cuisine that has withstood the sands of time. Let the feast begin!

Mostly desert, the Nile Delta hosts the majority of agricultural land and only 2-8% of the country's territory is arable. Egypt's main agricultural products are wheat, beans and fruits. Egyptian cuisine makes heavy use of poultry, legumes, vegetables and fruit.

Ancient Egyptian food spans more than three millennia, although many of its characteristics persisted far into the Greco-Roman era. Bread and beer were mainstays for both affluent and poor Egyptians, typically served with various vegetables, meat, and fish to a lesser degree, and green-shooted onions.

Although it can include meats, particularly squab, chicken, and lamb, Egyptian cuisine mostly focuses on vegetables and lentils. The diet of the ancient Egyptians included wheat, barley, and rice, yet the sources are ambiguous on millet. Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi said that it was unknown outside of a tiny region of Upper Egypt where it was grown. Muhammad ibn Iyas, the chronicler, seems to corroborate this, noting that millet intake was rare, if not unheard of, in Cairo. Conversely, according to Shihab al-Umari, it was one of the most widely eaten cereal grains in Egypt at the time.

An Egyptian tale from the Thousand and One Arabian Nights called The Tale of Judar and His Brothers tells the story of Judar, a poor fisherman, who discovers a magic bag pertaining to a Maghrebi necromancer. This bag provides its owner with prepared stock, tail fat, and rice dishes like aruzz mufalfal, which is spiced with cinnamon and mastic and occasionally coloured with saffron.

|

| The Tale Of Judar and His Brothers |

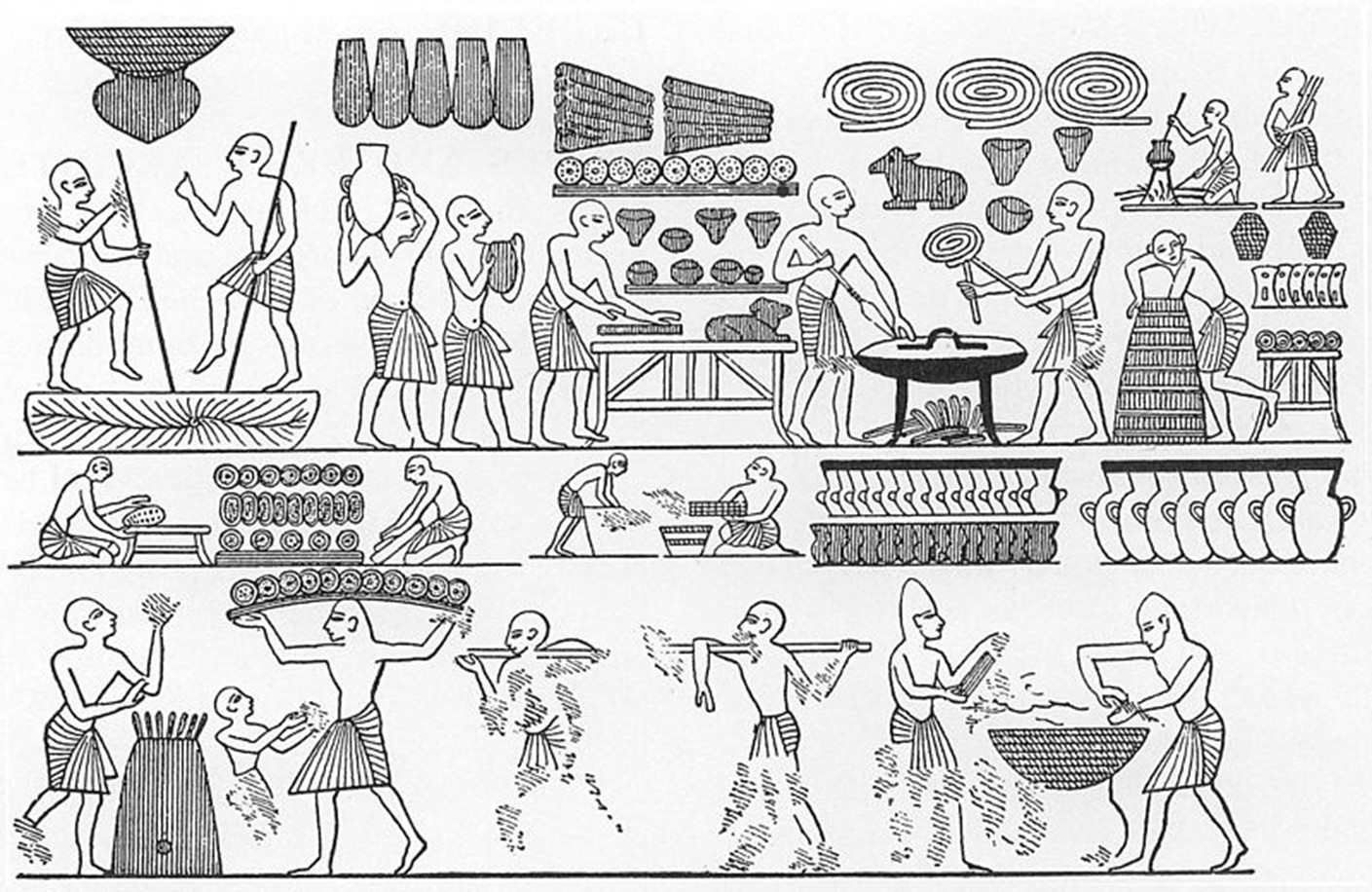

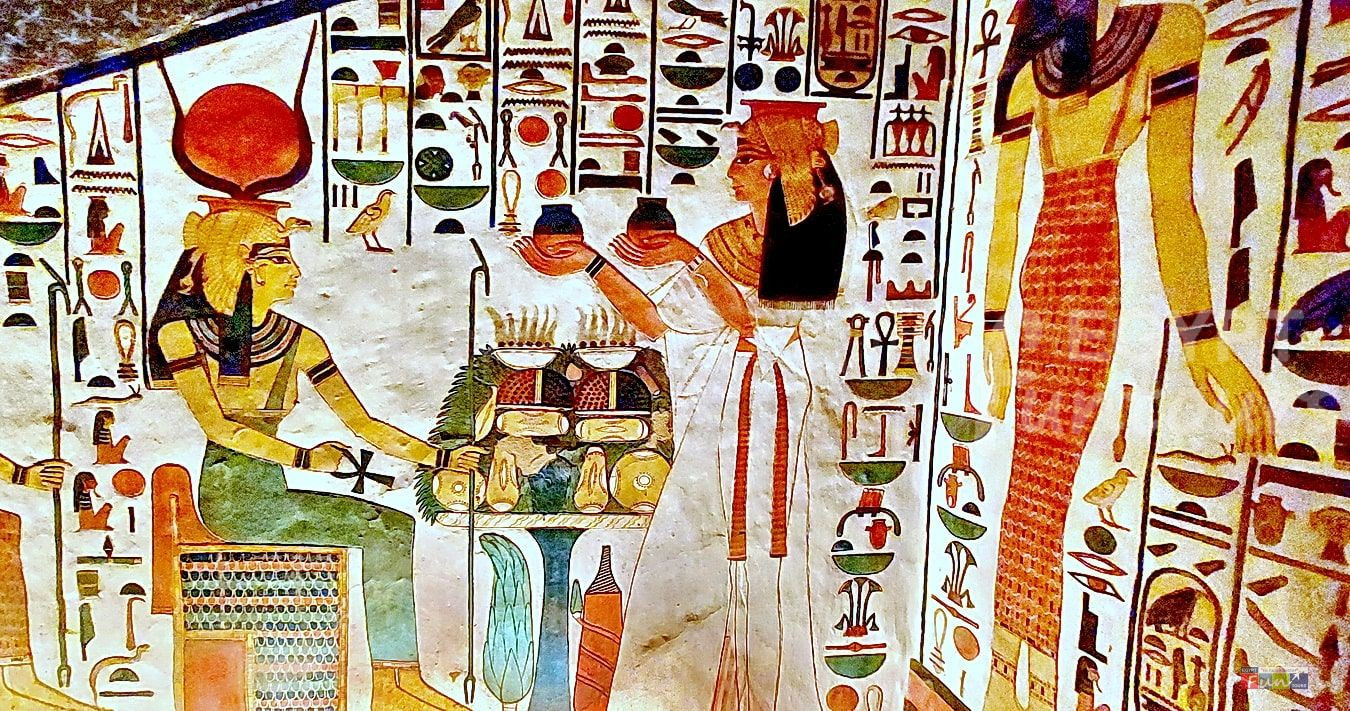

In addition to bread and beer, the poor also consumed fruit, vegetables, and fish in the ancient Egyptian diet. It has several sculptures from the Old and New Kingdom eras that depict food.

THE KITCHEN:

Cooking was the domain of women and girls, unless they lived in big houses with male bakers and cooks. Making lunches for the men and boys to take to work or school was a part of their job. Typically, the kitchen was an open yard at the rear of the house equipped with a grindstone, a wood-fired oven and pots for storage. There were no dishes, and people ate with their fingers from trays or baskets. During communal meals, the family would gather around the table and assist themselves, but during large gatherings, attendants would serve food and beverages to the attendees.

Despite the fact that we know so little about Ancient Egypt, the tools, pottery, and hieroglyphics that have been found over time have given us a basic sense of what their kitchens looked like and the kinds of instruments that they employed. The kitchen was an important part of Ancient Egyptian civilization, as is often the case.

It varied greatly in size and shape from house to house, temple to palace. It might be a big space inside a castle, or it can be the lone room in a modest house. The Egyptians utilised rather basic tools. For grinding, they used pots and pans, ovens, mortars, metal blades, urns made of stone and clay, baskets, pans, plates, pitchers, sieves, and pestles.

FEATURES:

Due to its heavy reliance on vegetable and legume dishes, Egyptian cuisine is particularly well-suited for vegetarian diets. Egyptian cuisine is mostly centred on items that grow out of the ground, yet meals in Alexandria and along Egypt's coast frequently uses fish and other shellfish.

The principal ports of entry for spices into Europe were located in Egypt's Red Sea region. Over time, Egyptian cuisine has been influenced by the ease of obtaining a wide variety of spices. The most widely utilised spice is cumin. Coriander, cardamom, chili, anise, bay leaves, dill, parsley, ginger, cinnamon, mint, and cloves are some more frequent spices.

Duck, chicken, and pigeon constitute typical meats eaten in Egyptian cuisine. They are frequently cooked to create the broth for different soups and stews. The most popular meats to grill are beef and lamb. All grilled meats are called mashwiyat, including kabab, kofta, and grilled cutlets.

In Egypt, offal, or variety meats, are quite popular. Alexandrian-style liver sandwiches are a common fast-food item in urban areas. Slices of chopped liver, cooked with bell peppers, chile, garlic, cumin, and other spices, are served on a bread called eish fino that resembles a baguette. Egypt eats the brains of cows and lambs..

The famous delicacy foie gras is still relished by Egyptians today. Its flavour, in contrast to that of a typical duck or goose liver, is characterised as rich, buttery, and delicate. Foie gras can be purchased whole or made into mousse, parfait, or pâté. It can also be offered as an accompaning dish, like steak, for another dish. The method, known as gavage, was first used by the ancient Egyptians to stuff food down the throats of domesticated ducks and geese around 2500 BC..

Now, here comes the fun part! I've grouped information based on food categories, and you're sure to love the colorful palette. In this section of the blog, I'm discussing the consumption of fruits and vegetables, followed by various types of meat and fish. Lastly, we'll explore bread and cheese. Let's dive in:

FRUITS AND VEGETABLES:

In addition to their regular usage as a side dish for beer and bread, vegetables were also consumed for their medicinal properties. The most popular vegetables were garlic and long-shooted green scallions. In addition, there were lettuce, celery (raw or cooked in stews), several varieties of cucumber, maybe some Old World gourds, and even melons. Turnips existed by Greco-Roman times, while it's unclear if they were around before then. Nutrient-rich sedge tubers, such as papyrus, might be consumed raw, cooked, roasted, or crushed into flour.

Sweet potatoes (Cyperus esculentus) were crushed, dried, and combined with honey to produce tiger nut desserts. Lilies and other related blooming water plants have edible roots and stems that could be eaten raw or ground into flour. Peas, beans, lentils, and chickpeas were just a few of the pulses and legumes that were essential sources of protein. As early as the 4th Dynasty, olive oil was transported and stored in ceramic pots brought from the Middle East, according to the excavations of the workers' settlement at Giza.

In addition to figs, grapes (and raisins), dom palm nuts (either eaten raw or steeped to create juice), several species of Mimusops, and nabk berries (jujube or other members of the genus Ziziphus) were among the most often seen fruits. Figs were quite popular since they had a lot of protein and sugar. The dates would be consumed fresh or dried/dehydrated. Dates were utilised as sweets by the impoverished and were even used to make wine. Fruit was more seasonal than vegetables, which were farmed all year round. Grapes and pomegranates would be placed in the deceased's graves.

MEAT AND FISH:

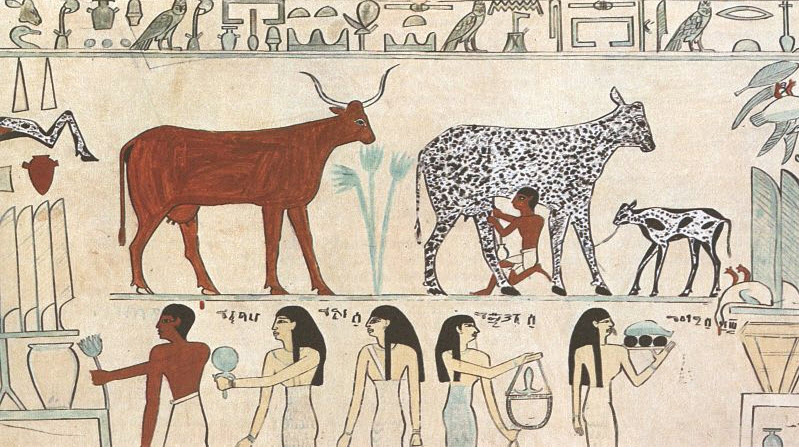

Game, poultry, and tamed animals provided the meat. Partridge, quail, pigeon, ducks, and geese may have been among them. Though no chicken bones have been discovered that date from before the Greco-Roman era, the chicken most likely originated in the fifth or fourth century BC. Cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs were the most significant animals; before, it was believed that eating pigs was forbidden as Egyptian priests associated them with the malevolent deity Seth.

Greek historian Herodotus said in the fifth century BC that the Egyptians refused to eat female cows because they were associated with the goddess Isis. After it was ceremoniously burnt, they consumed the remaining male cattle that had been slaughtered and examined to ensure they were healthy. Male oxen that were sick or sickly and deemed unfit for sacrifice were buried in a ritualistic manner. Their bones were then cleaned and reinterred in a temple. The Greeks in Egypt were forbidden from consuming the flesh of the sacred sacrifice, therefore the only food accessible to them was the heads of the male bulls that were severed and thereafter cursed. Due to evidence of widespread ox, mutton, and hog slaughter found during excavations at the Giza worker's hamlet, scientists believe that the labour force that built the Great Pyramid was given meat on a daily basis.

Despite the claims made by Herodotus that swine were unclean and should be avoided, mutton and pork were more frequent. Except for the most impoverished, everyone had access to fish and poultry, both domestic and wild. Legumes, eggs, cheese, and the amino acids found in bread and beer would have been preferable substitute sources of protein. Hedgehogs were also consumed, and one popular method of cooking them was to bake them whole by encasing them in clay. The thorny spikes were removed along with the clay when it was broken apart.

The ancient Egyptians created foie gras, a well-known delicacy that is still eaten today. The practice of gavage, which involves jamming food into the mouths of tamed ducks and geese, was first used by the Egyptians 2500 BC when they started rearing birds for sustenance.

A book from the 14th century, which was translated and released in 2017, has ten recipes for sparrow, which was consumed for its aphrodisiac qualities.

BREAD:

Egyptian cuisine is centred around a particular kind of pita bread called eish baladi. Since emmer wheat was more difficult to mill into flour than most other types of wheat, it was used nearly exclusively in Egyptian bread. Instead of being removed by threshing, the chaff arrives in spikelets that must be broken free by wetting and pounding with a pestle in order to prevent crushing the grains within. After that, it was sun-dried, winnowed, sieved, and ultimately milled on a saddle quern, which worked by bouncing the grindstone back and forth as opposed to turning.

The court bakery of Ramesses III

Over time, baking methods changed. Dough was placed within large ceramic moulds in the Old Kingdom and baked there in the flames. Square hearths were equipped with tall cones throughout the Middle Kingdom. A novel kind of big, cylindrical clay oven with an open top that was covered in thick mud bricks and mortar was utilised in the New Kingdom.

The dough was then placed on the hot inner wall, just like flatbreads are placed in a tandoor oven, and when it was done, it was pulled off. Images of bread in a variety of sizes and forms have been found on tombs from the New Kingdom. Dough was used to create loaves shaped like fish, fans, animals, and human figures. Bread flavourings included dates and coriander seeds, however it's unclear if the impoverished ever utilised them.

Aside from emmer, other crops planted for bread-making included barley, tiger nuts, and the seeds and roots of lilies. Because it wore down the enamel, the grit from the quern stones used to mill the wheat incorporated with bread was a primary cause of dental disease. There were also exquisite dessert breads and cakes made with premium flour available for the wealthy.

Reviving a Nasser-era programme, the government currently subsidises bread in Egypt. A severe food crisis in 2008 resulted in increasingly lengthy lineups for bread in government-subsidized bakeries where none would typically exist; sporadic altercations over bread led to 11 fatalities in 2008.

Bread is frequently used as a tool in cooking and contributes protein and carbs to the Egyptian diet. Egyptians wrap kebabs and falafel in bread to prevent their hands from getting oily and to scoop up food, sauces, and dips. The flattened dough rounds puff up substantially when cooked at high temperatures (450 °F or 232 °C), as is the case with most pita breads. The cooked dough layers within the deflated pita stay apart when the bread is taken out of the oven, enabling it to be opened into pockets and used in different recipes.

CHEESE:

Cheese production in Egypt has been around since the First Dynasty, with the most widely consumed form being domiati.

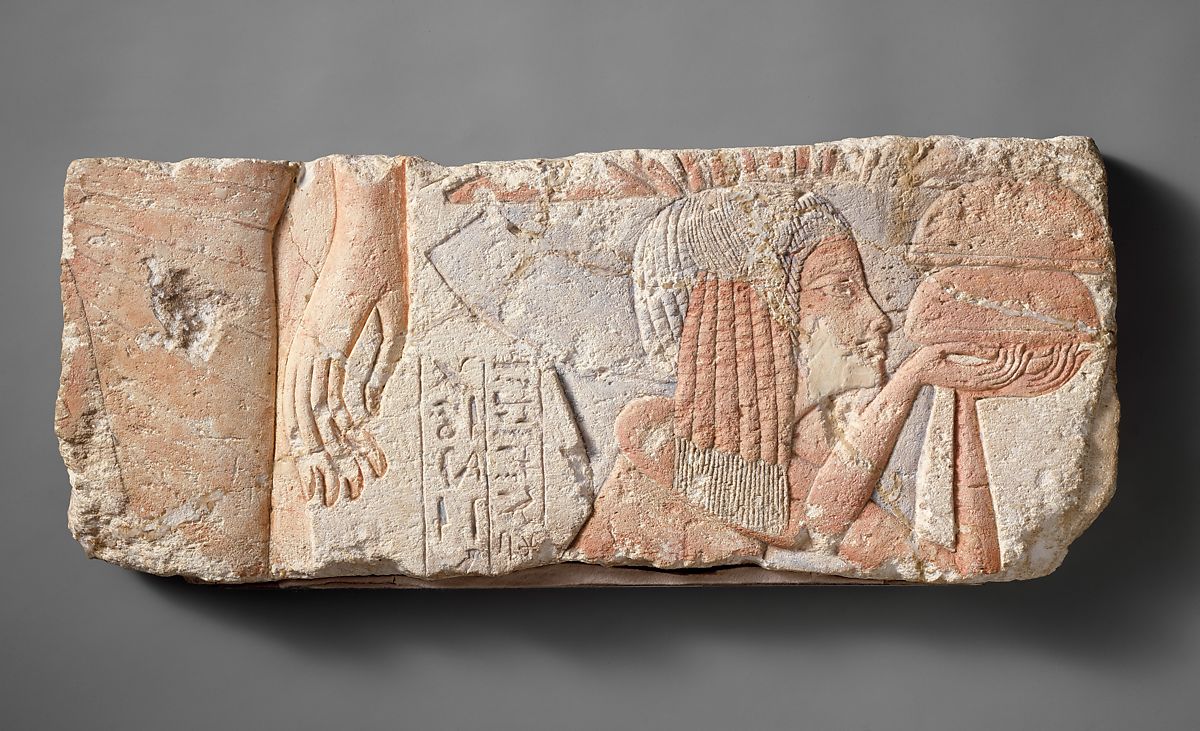

Middle Eastern cuisine is regarded to be the birthplace of cheese. Two First Dynasty Egyptian alabaster jars discovered in Saqqara held cheese.About three thousand BC, these were buried in the tomb. They were probably fresh cheeses that had been heated and/or acid-coagulated. Cheese that appears to be from Upper and Lower Egypt based on the hieroglyphic inscriptions on the two jars may have also been found in an older tomb belonging to King Hor-Aha. The pots are comparable to ones that are used now to make mish.

Mass-produced cheeses are becoming more widely available, even though many rural people continue to produce homemade cheese, particularly the fermented mish. Cheese is a common breakfast accompaniment as well as a component of many classic recipes and desserts. Cheeses include rumi, a hard, salty, matured type of cheese that is related to Pecorino Romano and Manchego; areesh, manufactured from laban rayeb; and domiati, the most popular cheese in Egypt.

So, that's a tasty glimpse into the fascinating world of ancient Egyptian food! From The kitchen style to veggies and fruits to meats and bread, we've uncovered a delicious history that goes back thousands of years. But hold on, we're not done yet! There's more to explore, more flavors to savor. Next week, I'll be back with the second part of this adventure. Get ready for another round of mouthwatering discoveries as we continue our journey through the ages of Egyptian cuisine. Stay tuned, food enthusiasts – the feast isn't over, it's just taking a short break!

Comments

Post a Comment