Maori Tattoos: A Global Journey Through Time and Tradition

A Polynesian tattoo is referred to as "E Patu Tiki" in the Marquesas islands' unique language, which means "in order to strike an image." This is acknowledged as the location of the most elaborate and complex designs.

Ta Moko designs have historically been different for males (Taane) and women (Whaea). Painting Mataora on their faces was considered a sign of grandeur for men. Tattoos on the face have great meaning for the Māori, who consider the head to be the most holy portion of the body.

Types of Maori Tattoo:

Three kinds of tribal tattoos were identified: the tattoos for male and female chiefs, those reserved for gods, priests, and princes, which were inherited and thus only visible on their offspring; and the third kind, which was exclusive to warriors, war chiefs, dancers, and rowers.

Some of the patterns were meant to ward against bad powers and prevent people from losing their mana, the divine power that governs reproduction, health, and balance. In Marquesan Island culture, getting a tattoo was not only considered a privilege but also an obligation that had a profound effect on people's life and served as a link to the revered memories of their ancestors. And since it was enduring, the work would eventually serve as a testament to their beginnings, status, and bravery when they were called upon to make an appearance before their ancestors—the gods of the mythical "Hawaiki"—in the hereafter.

When missionaries converted the king to Catholicism in 1819, they introduced the Pomare code, which forbade Polynesian tattooing throughout the islands and destroyed much of its history. The 1980s witnessed a resurgence of it, and although the religious constraints subsided, the underlying symbolic force—to the indelible imprint of a memory, an event, or a tale on the skin—persisted.

More than ever, Polynesian tattoos serve as a means of expressing one's identity and dedication to the culture, with tattoo artists honing their skills to replicate traditional motifs, decorative motifs (like dolphins or manta rays), and—most recently—to create entirely original motifs that draw directly from tradition.

Tricks and Techniques of Maori Tattooing:

Tattoo artists went by the names "tahua'a tatau" in the Society Islands and "tuhuka (or tuhuna) patu tiki" in the Marquesas. Their objective was to make a lasting effect on every community member at every stage of their lives.

Since the painters' trade was usually passed down from father to son, they needed to be very skilled teachers. Mallets were used in combination with sharp combs made of bone, tortoiseshell, or mother-of-pearl that were attached to wooden handles.

Ink made from diluted candlenut (Aleurites Moluccana) charcoal in either water or oil was applied to the comb's teeth. How much surface area needed to be covered dictated how many prongs the comb should have.

Two to twelve prongs may be seen, however individuals have claimed seeing as many as thirty-six. Before using ink, the tattoo artist would draw the design on the wearer's body using a charcoal stick. As a result, the tattooing ceremony evolved into a serious ritual that was conducted to the sound of drums, flutes, and conch horns. Some families found it costly, using all they owned—including battle mallets, painted bark cloth, pigs, and tapa—to pay for the tuhuka. Because of this, a large number of people at the bottom of the socioeconomic scale were unable to buy numerous tattoos.

What led to the rise in popularity of Maori tattoo art?

Captain James Cook, a native of Eastern Polynesia, introduced the Maori tattoo art to New Zealand in 1769. It was determined that Cook borrowed the term "tattow" from the Tahitian word "tautau." During their trip to the South Pacific, Captain Cook and Joseph Banks first noticed the elaborate tattoos of the Maori people, which immediately captivated and enthralled them.

The Maori tattooing tradition piqued the curiosity of European explorers visiting New Zealand. During battle, Maori would frequently capture the tattooed heads of their adversaries as trophies and preserve them in elaborate cases as representations of their strength, victory, and defence. A group of missionaries later took the decision to study Maori and attempt to convert them to the ideas of Christianity since Europeans made frequent contact with Maori tribes. With a leader named Hongi in tow, the Europeans sailed back to England in 1814.

On the way home, in Sydney, Hongi traded his presents for a bunch of muskets and a large cache of ammo. He utilised the weapons to conduct a number of raids against opposing tribes after arriving back in New Zealand. Later on, the Maori found out that the Europeans were actually trading Maori skulls with tattoos for weaponry.

In due course, the Maori people would indeed invade nearby tribes with the express intent of taking tattooed heads in exchange for additional ammunition and firearms. Afterwards, the dealers offered the heads for sale to European museums and individual buyers.

In their fervent quest for arms, the Maori would decapitate and tattoo the skulls of slaves and commoners they captured during combat. Frequently, incomplete tattoos or heads of inferior quality were also for sale.

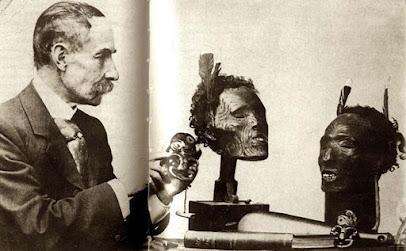

Major General Horatio Robley was a well-known collector of tattooed skulls, having amassed about 35 throughout his lifetime. Currently housed at the Natural History Museum of New York are thirty of the thirty-five skulls that were part of his collection. The book Moko, written by Major General Robley, provided comprehensive information on the creation and significance of Maori tattoo patterns.

Tattoo symbols and their meanings:

One's work and family structure also influence the tattoo's placement. A teacher could acquire a face tattoo on their lower lip, called a moko, while a masseuse can receive tattoos on her hands. Abstract and geometric patterns in the shapes of rectangles, circles, and crosses, along with realistic representations of animals and plants, were frequently seen on the arms, legs, and shoulders.

In Marquesan tattoos, human figures—known as "enata"—were used to symbolise family members or other individuals. The sign has personal and relational implications, and it might symbolise a man or a woman or a celestial figure. Enata sometimes takes the shape of a group of people holding hands when arranged in a pattern; a row of enata in a semicircle often symbolises the sky and the ancestors watching over their living kin. Inverted enata might stand for vanquished adversaries.

Shark teeth have triangles on them and are quite sharp. They stand for bravery and selflessness. They stand for many different qualities in numerous civilizations, including ruthlessness and adaptability, as well as things like leadership, shelter, and energy.

Utilised to symbolise the warrior within you, the spearhead is an age-old emblem of war, combat, animosity, and victory. Within the warrior class of the tribe, it was common knowledge that an arrow pointing in the same direction signified defeat of the enemy. It is also said to stand for defence, tenacity, and even an animal's sting.

The seas are often believed to be a conduit between the material and spiritual realms, symbolising the tides of life and death and having a profound impact on a multitude of mythologies and cultural practices. The waves are the ocean's emblem, and for the Polynesians, the water is a place of rest in the afterlife, much like it is for many other civilisations.

Representing a half-god, half-human being that is the ancestor of humans, the tiki (the first person to become a worshipped ancestor) had a significant effect on Marquesan style. It protects the wearer from harm and evil spirits and also communicates power and masculinity. It also functions as a fortunate charm. Tiki can also stand for priests, chiefs, and other deified ancestors who attained a semi-godly status after death. They act as guardians and are symbolic of fertility and protection.

The most significant emblem of the tribe and the cohesion of the family, the turtle is a popular motif in Polynesian tattoo designs. A major creature in Polynesian culture, they are connected with virility, vigour, endurance, and power. In life, they stand for immortality and calmness.

In Polynesian culture, lizards are significant and have many meanings. Because of their reputation for overcoming hardship, they serve as a force that protects both men and women from bad luck and other omens. In order to communicate with the gods, folks commonly call upon gods (atua) in the guise of geckos and lizards. They possess the ability to destroy, are skilled fortune tellers, and have connection to the spiritual realm.

Similar to stingray tattoos, dolphin tattoos stand for liberation. According to Polynesian tradition, the dolphin shielded the Māori from sharks and led them to the promised land. Both Polynesians, this animal is significant since it stands both protection and direction.

Currently, Māori tattoo artists are present on almost every major inhabited island in French Polynesia. Due to their fame and the beauty of the Polynesian tatau, visitors travel from all over the world. Polynesian tattoos are well-known across the world for their genuine cultural appeal and traditional origins, thus you may find tattoo artists from this region in many major cities.

Comments

Post a Comment